Following the Blockchain.com feerate recommendations

Wallet fingerprinting nearly a third of all Bitcoin transactions

Monday, July 13, 2020Transactions sent with Blockchain.com wallets make up for about a third of all Bitcoin transactions. A methodology to identify these transactions is described and used. Insights about the wallet-usage are derived from the resulting dataset. The privacy implications and possible improvements are discussed.

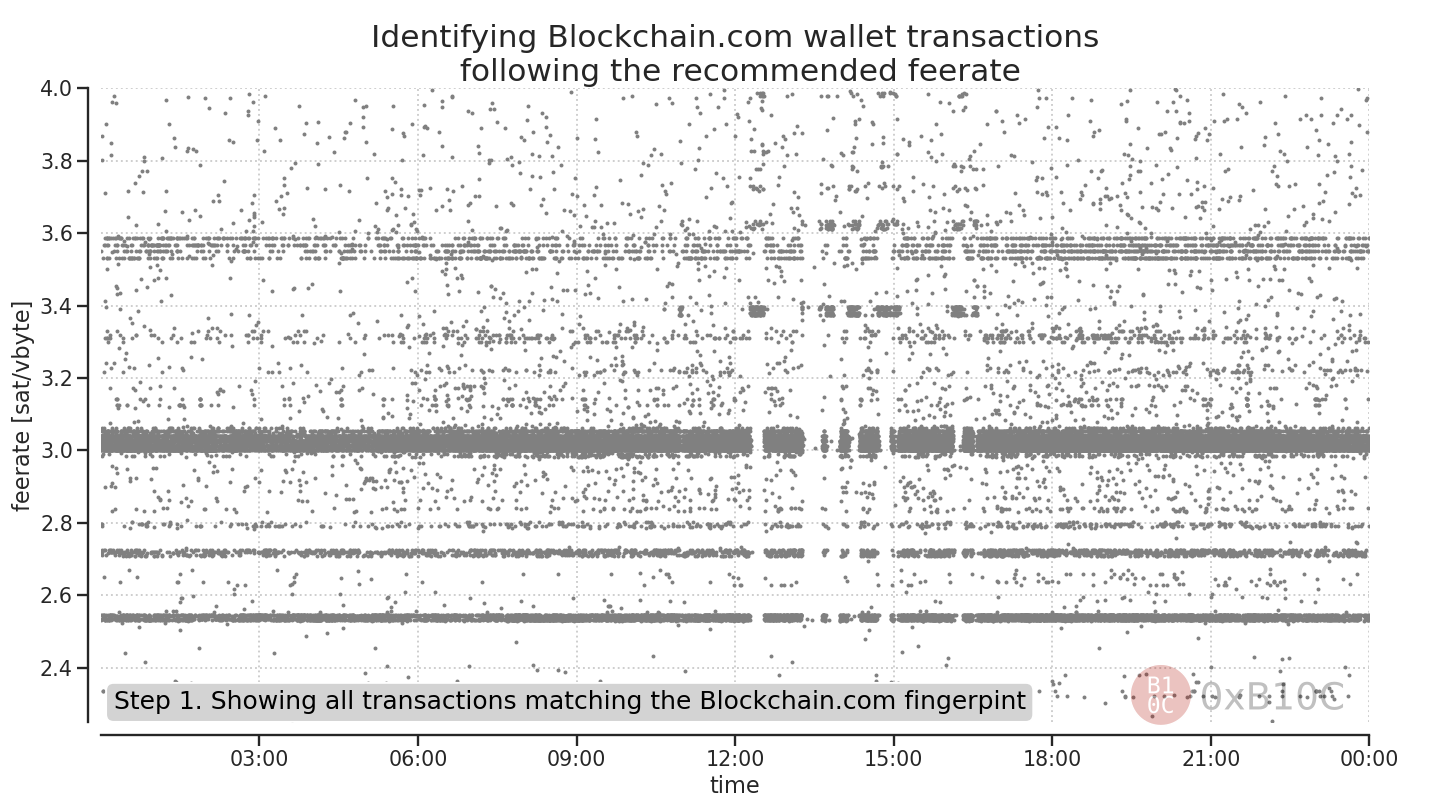

One of the first observations made when building the Bitcoin Transaction Monitor was that many transactions precisely follow the recommendations of a feerate estimator. These transactions appear as horizontal bands, which rise and sink as the feerate recommendations change.

Most of these transactions share the same fingerprint. Only P2PKH outputs are spent. No SegWit and neither multisig are spent. With every transaction, either one or two outputs are created. When two outputs are created, then at least one of them is a P2PKH output. The transactions are not time-locked, have a version of one, and do not signal BIP-125 replaceability. However, all are BIP-69 compliant.

This matches the fingerprint of the Blockchain.com wallets: namely a Web, an iOS, and an Android wallet. The wallets can only receive and spend P2PKH outputs. While users can pay to all address formats1, the change-output, if created, is a P2PKH output. The wallets construct the transactions with a locktime of zero and a transaction version of one. The inputs and outputs are all lexicographically sorted as specified by BIP-69.

The wallets use the Blockchain.com feerate estimator, which is publicly accessible via an API. The API returns two feerate estimates: priority and regular. The priority feerate aims for confirmation in the next hour and the regular feerate for confirmation in an hour or more. By default, the wallets follow the recommendations closely. Users can set a custom feerate, but a warning is displayed.

Methodology

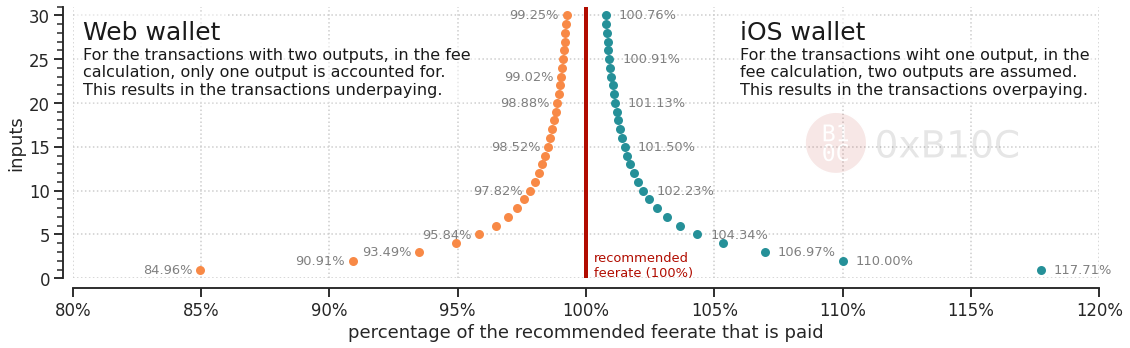

Combining the feerate estimates and the transaction fingerprints makes it possible to identify transactions sent with one of the Blockchain.com wallets. While the majority of the Blockchain.com transactions pay exactly the recommended feerate, some under- or overpay by a fixed percentage. This is caused by incorrect assumptions about the transaction size during the calculation of the transaction fee. The transaction fee is the product of the targeted feerate and the assumed transaction size. The final and actual transaction size is only known after adding the signature to the transaction.

fee = target feerate × assumed transaction size

All underpaying transactions have two outputs. However, during the fee calculation, the size of a one-output transaction is assumed. For example, for a P2PKH 1in ⇒ 2out transaction (226 bytes), the size of a 1in ⇒ 1out transaction (192 bytes) is used. This incorrect assumption results in the transaction only paying around 85% (192 byte / 226 byte) of the recommended feerate. As the transaction inputs make up for a large part of the transaction size, the effect is smaller for transactions with more inputs. This behavior was only present in the Blockchain.com Web wallet. A fix was released on April 21st, 2020.

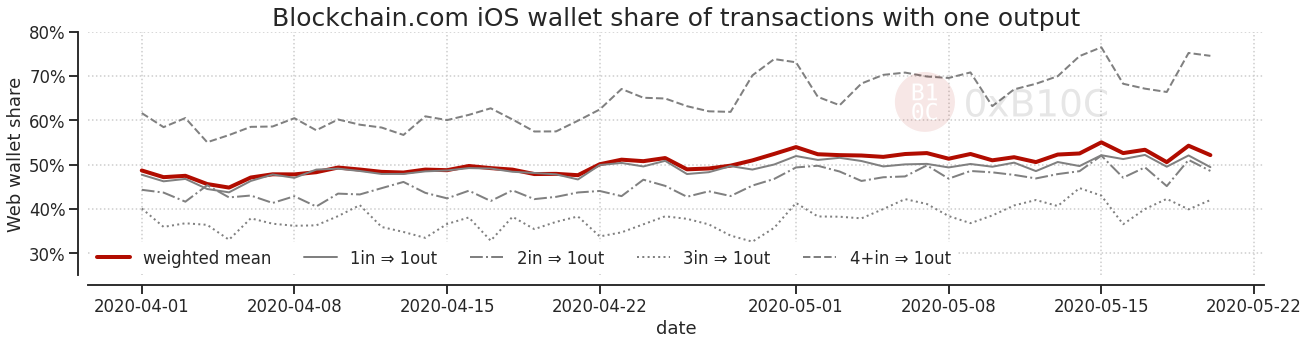

The overpaying transactions all have a single output. For these, a second output is assumed during the fee calculation. To calculate the fee of a P2PKH 1in ⇒ 1out transaction (192 bytes), the size of a 1in ⇒ 2out transaction (226 bytes) is used. This results in the transaction paying about 118% (226 byte / 192 byte) of the recommended feerate. Similar to the underpaying transactions, the effect is smaller for transactions with more inputs. These transactions are assumed to originate from the Blockchain.com iOS wallet. This has not yet been confirmed.

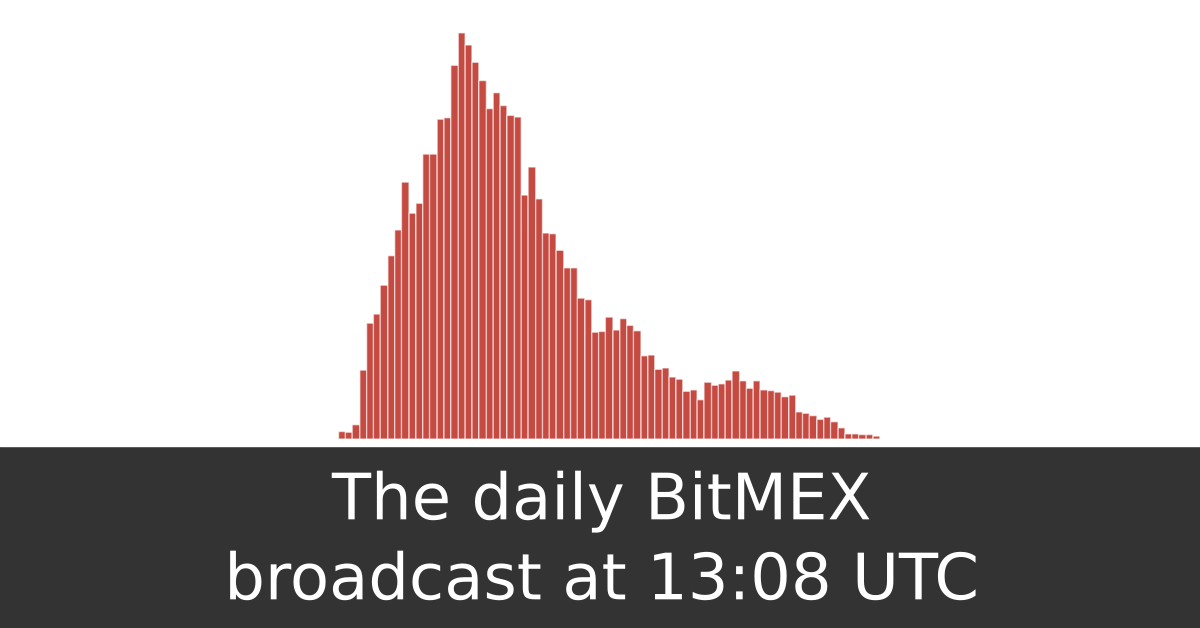

Identifying Blockchain.com wallet transactions with this methodology is not assumed to be perfectly accurate or reliable. For example, transactions send with a custom feerate can not be identified and are false negatives. Transactions constructed by different wallets that pay a similar feerate and share the fingerprint could be identified as false positives. When the recommended feerate is volatile, which is often the case for the priority recommendation (for example, shortly after the daily BitMEX broadcast), then some transactions might pay a feerate not recoded by the Bitcoin Transaction Monitor. Additionally, the wallets could construct a transaction using an older recommendation, which is different from the recommendation at the time the transaction is broadcast. These transactions are false negatives as well.

Observations

The described methodology is used to identify the transactions send with Blockchain.com wallets between April 1st and May 20th, 2020. The resulting dataset spans over 50 days and contains about 4 million transactions. These pay a total fee of 445.73 BTC and account for about 1.34 GB of block space. Roughly two-thirds of the Blockchain.com wallet transactions target the regular feerate while the remaining third targets the priority feerate.

Roughly the same number of outputs are created as are spend. Blockchain.com wallet transactions have either a single payment-output or a payment-output and a change-output. As the change-outputs are always P2PKH outputs, it is possible to determine the payment-output type. Out of all outputs created about 31.7% are P2PKH, 23.3% are P2SH, 0.34% are P2WPKH, and less than 0.01% are P2WSH payment-outputs. The remaining 45.5% are P2PKH change-outputs. The most commonly used input-output combinations are P2PKH ⇒ P2PKH + P2PKH with 33%, P2PKH ⇒ P2SH + P2PKH with 26%, and P2PKH ⇒ P2PKH with around 7%.

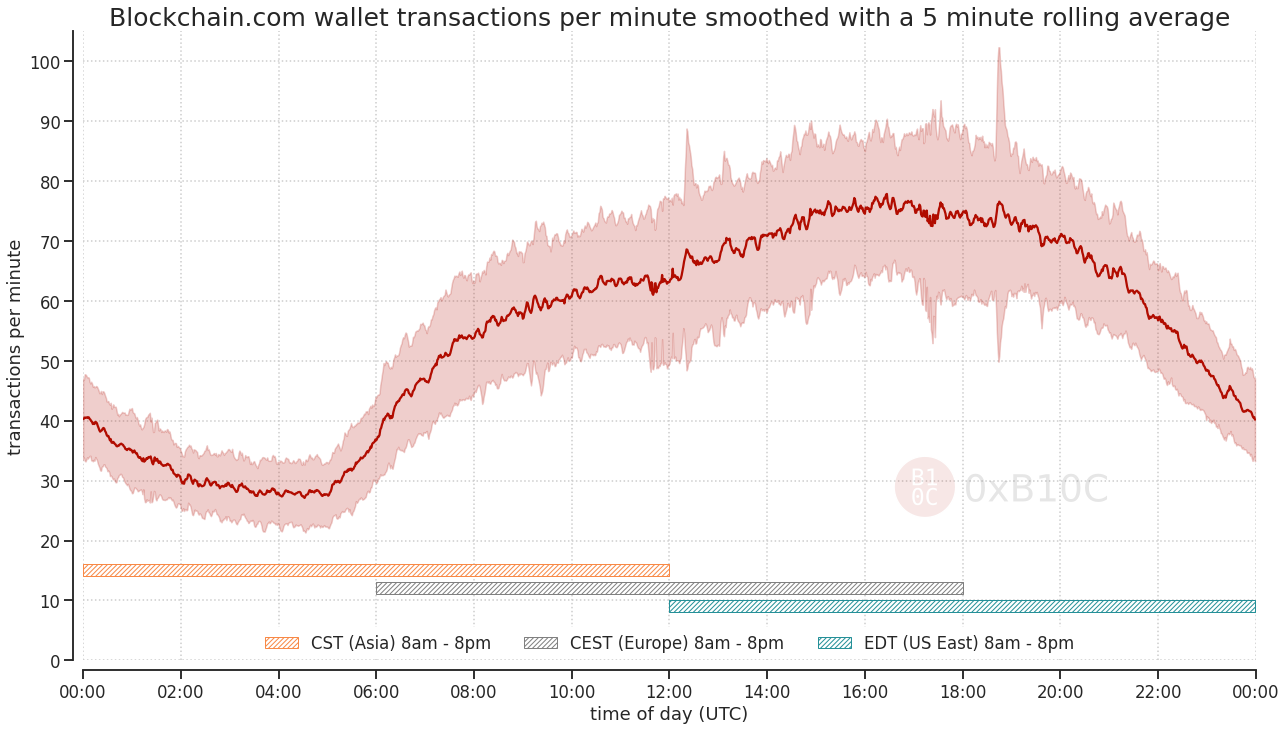

Users of the Blockchain.com wallet are most active between 15:00 UTC and 18:00 UTC and least active between 4:00 UTC and 5:00 UTC. At around 5:00 UTC, the number of transactions per minute starts to rise. At this time it is 8am in Moscow, and 7am in central Europe. Between 5:00 UTC and 10:00 UTC, the number of transactions per minute rises from about 30 to just above 60. The transactions per minute remain constant until rising again at noon UTC, which is 8am on the US east coast. The daily maximum is reached at around 16:00 UTC with just above 75 transactions per minute. From there on, the activity declines until reaching the minimum number of transactions per minute at around 4:00 UTC again.

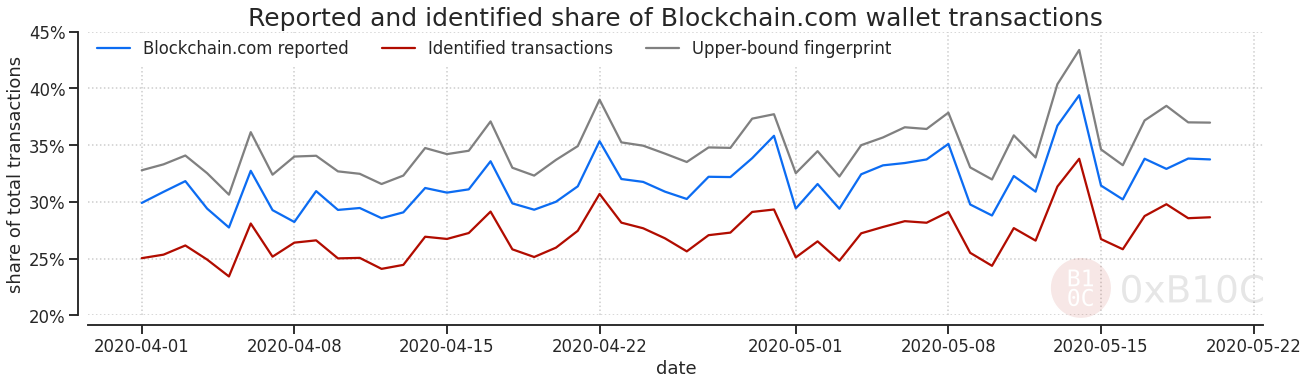

Reportedly, Blockchain.com claims that their wallets are responsible for one-third of all Bitcoin transactions. They publish the daily number of transactions sent by their wallets. This lead to a discussion on the accuracy and correctness of these numbers. The described dataset can be used to verify this claim. The number of daily transactions in the dataset and the published numbers can be compared. The total number of transactions sharing the fingerprint with the Blockchain.com wallet transactions acts as an upper-bound. The total transactions per day are retrieved from transactionfee.info to calculate Blockchain.com’s share of the network.

The daily transaction count published by Blockchain.com translates into a network share of 30% to 35%. The share of the transactions with the same fingerprint, the upper-bound, is on average about three absolute percent higher. The share of the identified transactions in the dataset is about four to five absolute percent lower than the Blockchain.com reported numbers at around 27% on average. The transactions account for about 13% of the daily fees paid, and 20% of the daily block space used.

However, the numbers reported by Blockchain.com still lie in a reasonable range. There are multiple reasons why the described dataset could contain fewer transactions than are reported by Blockchain.com. Some users might send transactions with a custom feerate. These are not picked up by the described methodology. Furthermore, it’s not clear if the reported numbers include transactions send with the Blockchain.com Wallet API. The API allows users to construct transactions sending to multiple recipients which are not accounted for in the described dataset.

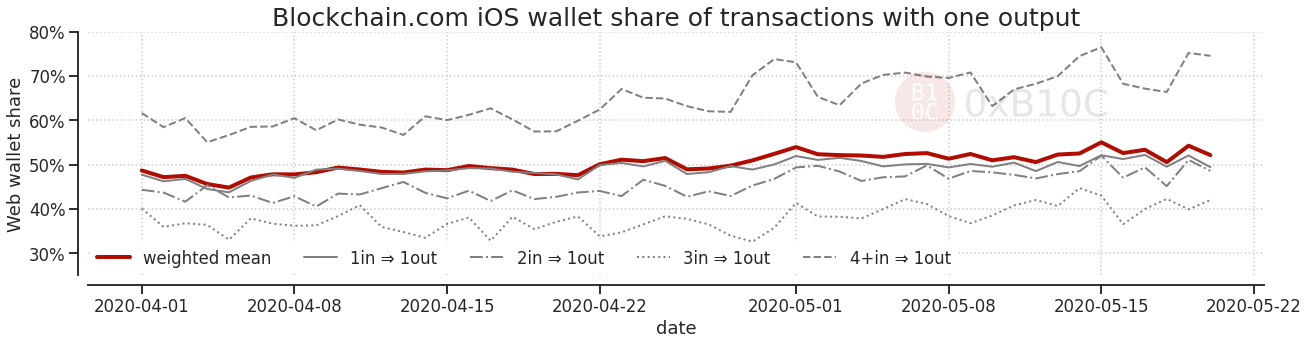

With the knowledge that the Blockchain.com Web wallet underpaid the recommended feerate for transactions with two outputs, and the iOS wallet overpays on transactions with one output, the wallet’s shares can be estimated. For this, the assumption that the ratio of two-output to one-output transactions is similar in all wallets must hold. The Web wallet accounts for one-third and the iOS wallet for half of the Blockchain.com wallet transactions. The Android wallet probably accounts for a majority of the remaining 17%. However, this can not be verified as no data is indicating the share of the Android wallet.

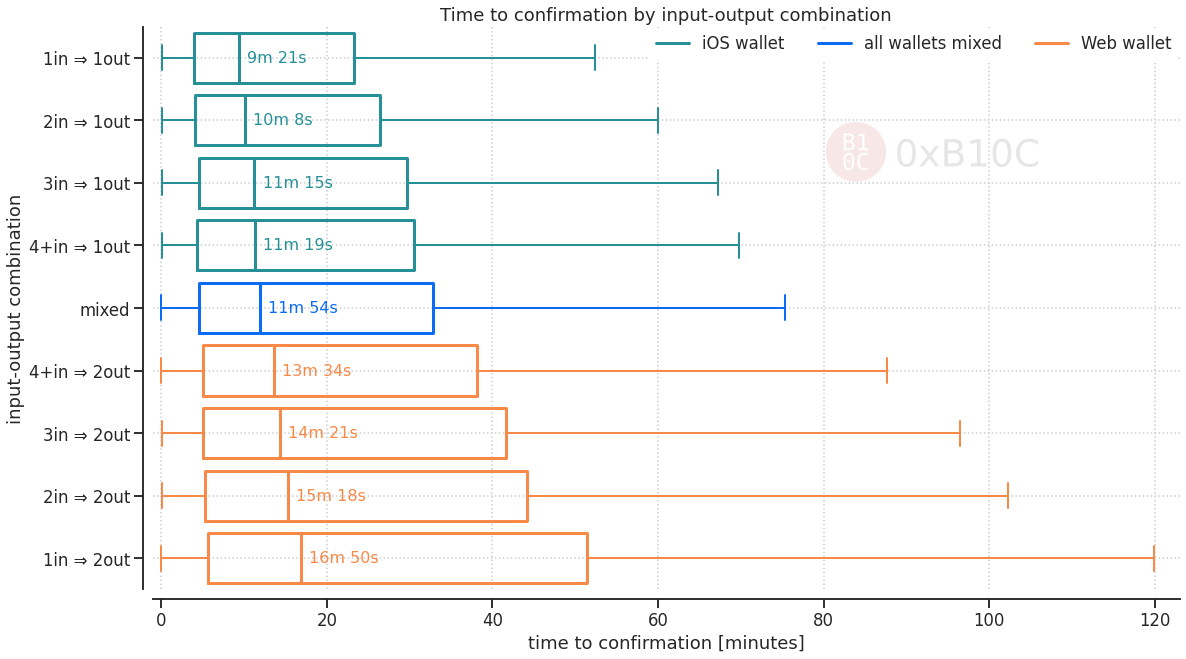

The iOS wallet overpays and the Web wallet underpaid the recommended feerate for some input-output combinations. This is noticeable in the time it takes for a transaction to confirm when targeting the regular feerate recommendation. The overpaying transactions fill up most of the block space, and transactions paying or underpaying the recommended feerate are only included in later blocks. In median, a one-output transaction send with the iOS wallet confirms the fastest. Two-output transactions sent with the Web wallet took the longest. The Web wallet’s effect was the strongest for transactions with one-input and two-outputs, which is the most commonly used input-output combination. These only paid about 85% of the recommended feerate. Transactions send with the Android wallet, iOS wallet transactions with two outputs or Web wallet transactions with one output confirm after the iOS wallet transactions with one-output and before the Web wallet transactions with two-outputs.

Paying a slightly higher feerate than the Blockchain.com iOS wallet pays for a one-output transactions could be a good trade-off between a fast confirmation and paying a low transaction fee. An advanced user could target a feerate of, for example, about 120% of the regular recommendation. A miner would include the transaction in a block before any of the Blockchain.com transactions are included. Targeting, for example, 102% of the regular recommendation could be an option too. This would be cheaper, but the transaction might take longer to confirm as the overpaying iOS wallet transactions confirm first. The effectiveness of these strategies might be reduced when the feerate recommendations are volatile during high activity hours.

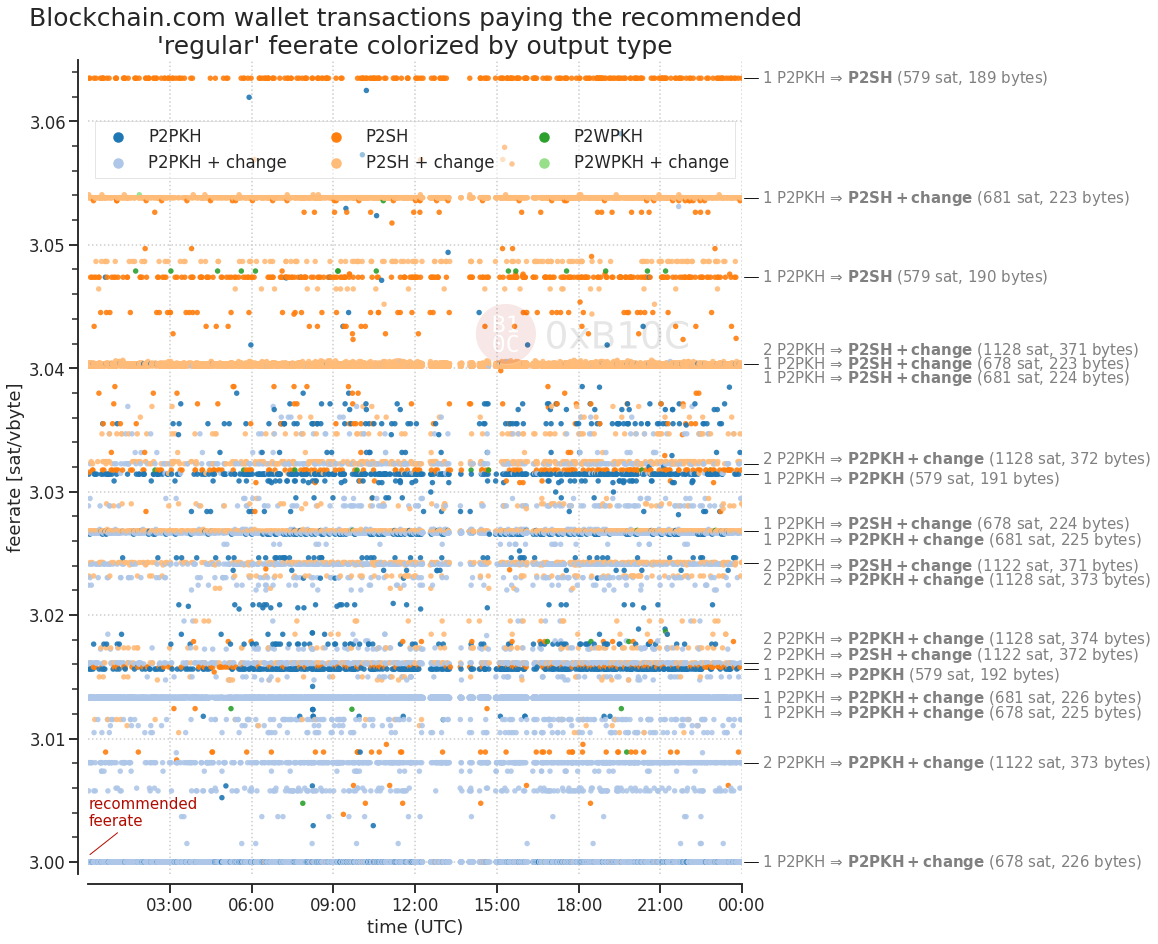

Taking a closer look at the transactions paying the recommended feerate shows transactions with P2SH outputs pay a slightly higher feerate than transactions with P2PKH outputs. In the Blockchain.com wallets, the assumed size of a single P2PKH output with 34 bytes is used in the fee calculation. P2SH outputs, with 32 bytes, are slightly smaller. Transactions with a P2SH output pay for two extra bytes, when the P2PKH output size is used. This results in transactions with P2SH outputs paying a slightly higher feerate. Something similar can be observed for transactions with a P2WPKH output, which have a size of 31 bytes. These pay for three bytes they do not have. P2WSH outputs take up 43 bytes, and thus transactions with a P2WSH output slightly underpay the recommended feerate as they are not paying for 9 bytes.

Users sending their funds to other wallets or services by creating a transaction that pays to a P2SH or a P2WPKH output unknowingly pay a minimally higher fee than they would have to. On average, these transactions confirm earlier. Transactions with P2WSH outputs pay slightly less than the recommendation and take longer to confirm on average. These effects are probably most noticeable during high activity hours.

Some transactions with the same input-output combinations appear multiple times at different feerates and have slightly different sizes. Low and high R-values in the ECDSA signatures can cause a one-byte size difference per input. Some transactions have the same input-output combination and the same size but pay a different fee, even when targeting the same feerate. This is caused by the iOS and Android wallet assuming a different P2PKH input size as the Web wallet. The Web wallet uses 147 bytes, and the Android and iOS wallet both use 149 bytes. P2PKH inputs are usually either 147 or 148 bytes. This depends on the R-value in the signature being either low or high. The sizes assumed by the Android and iOS wallet are incorrect. P2PKH inputs with 149 bytes were only possible when high-S values were allowed in the standardness rules before October 2015. More history on the lengths of ECDSA signatures can be found here.

Privacy

The more information a passive observer can derive from a Bitcoin transaction and public metadata, the worse the impact on the privacy of the sender and the recipient. Being able to identify the sending wallet is an information leak. To improve the privacy of Blockchain.com wallet users and to reduce the effectiveness of the described methodology, the recommended feerate should not be followed as closely, and the wallet fingerprint should be broadened.

A key part of reliably identifying Blockchain.com wallet transactions is to select the transactions that pay exactly the recommended feerates. By introducing randomness in feerates, the transactions mix with non-Blockchain.com wallet transactions. This increases the false-positive rate of the described methodology making it less reliable.

The term anonymity pool is used to describe the set of transactions with the same wallet fingerprint. The more wallets construct transactions with the same fingerprint, the harder it gets to identify the wallet a transaction originates from. This improves the privacy of all Bitcoin users. While the Blockchain.com anonymity pool consists of often more than 100000 transactions per day, the Blockchain.com wallets make up for at least 80% of these transactions. The fingerprint can be broadened in different ways, which increases the anonymity pool size and thus decreases the Blockchain.com’s share. This would have a positive effect on the privacy of Blockchain.com wallet users and the privacy of all other Bitcoin users. To broaden the fingerprint of the Blockchain.com wallet, it could, for example, support receiving to and spending from different address types, time-lock some of the created transactions to the current block height, or set a random transaction version when constructing the transaction.

For advanced users, it might be possible to hide their transactions in the anonymity pool of the Blockchain.com transactions. This could be done by mimicking the Blockchain.com wallet fingerprint and paying exactly the recommended feerate. If done correctly, somebody trying to wallet fingerprint transactions with the described methodology would false positively identify the transaction as sent by a Blockchain.com wallet. Blockchain.com could track which transactions were constructed by one of their wallets and which only try to mimic their wallets. This information could be sold to adversaries.

Personal note: I value the privacy of the individual. I won’t publish the transactions or txids I identified as Blockchain.com transactions. However, a motivated passive listener could easily use the outlined methodology to start tagging Blockchain.com users. I publish the above intending to raise awareness about the issue. Especially the awareness of Blockchain.com, users of the Blockchain.com wallets, and developers of other wallets closely following a feerate estimator. If you think I should have disclosed this privately before publishing it, please let me know - either in private or by calling me out publicly.

While my Mempool Observations are fun to write, the process is very time-consuming. You can support me here, which enables me to spend more of my time researching and writing. If you work for a company interested in improving your on-chain foot- and fingerprint, then I’d be more than happy to chat. If you are working on improving Bitcoin privacy, especially on removing wallet fingerprints, then I’d like to contribute the things I’ve learned starring at my Bitcoin Transaction Monitor. My contact information can be found at the bottom of this page.

I realized that I was not able to send to a bech32 P2WPKH address in the Android wallet when trying to withdraw funds used to test the wallet behavior. It is however possible to send to a bech32 address in the Web wallet. ↩︎